Introduction

When someone (loved one) is diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia, one of the first questions is about life expectancy. Families want to discuss how long their loved one might live, what changes to expect, and how to plan care.

The phrase “life expectancy for frontotemporal dementia patients” is important because it provides clear information. However, many online articles use shorter terms like “FTD life expectancy,” which can make it difficult for people to find useful answers. This may lead some to misunderstand or reject the terminology.

This guide will explain what life expectancy means in FTD, what affects it, and how families can prepare with confidence.

By the end, you will understand the frontotemporal dementia stages, life expectancy, see real factors that shape outcomes, and know practical steps to support the patients, families at home and their carers.

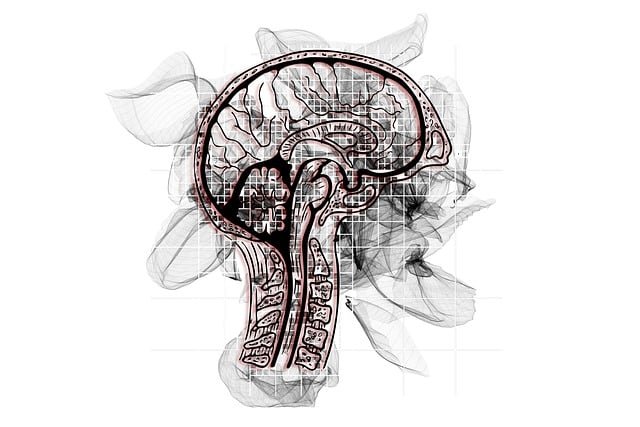

What Is Frontotemporal Dementia?

Frontotemporal dementia, or FTD, is a type of dementia that mostly affects younger adults. It damages the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. These areas control behaviour, language, and personality.

Unlike Alzheimer’s, FTD often starts earlier, sometimes in the 40s or 50s. It leads to strong personality changes, loss of speech, and eventually full dependence on carers.

Read: How to minimise risks of dementia

Because the illness affects behaviour and communication so strongly, it can feel very distressing for families. Understanding how long it might last can help prepare emotionally and practically.

Average Frontotemporal Dementia Life Expectancy

Studies show that most people live six to thirteen (6-13) years after symptoms first appear. Some live as few as three years, while others survive more than fifteen (15) years.

From the time of diagnosis, the average is often seven to eight years. This difference exists because symptoms often begin years before doctors recognise them.

Factors That Shape Life Expectancy

Type of FTD: The behavioural variant may last longer than the language or motor variants.

- Age of onset: Younger people may live longer but face earlier disability.

- Other illnesses: Conditions like motor neurone disease (directly affects all sorts of muscle movements in the body, ie, walking, talking, eating, breathing, etc.) can shorten life to just two or three years.

- Infections: Pneumonia and urinary infections are common causes of decline.

- Care quality: Supportive care may not cure, but it improves comfort and safety.

Frontotemporal Dementia Stages, Life Expectancy, and Practical Solutions

Unlike Alzheimer’s, there is no single universal system for frontotemporal dementia stages. Still, many experts outline seven broad stages. These stages are not exact, as every person is unique, but they give families a clear picture of what to expect. Understanding frontotemporal dementia stages and life expectancy helps families prepare for each step. With the right practical solutions, carers can ease stress and improve quality of life at every stage.

Stage 1: Early Subtle Changes

At the beginning, symptoms are very mild and often overlooked. The person may show small personality changes, such as acting out of character, being more withdrawn, or behaving in unusual ways. They may make poor decisions or forget simple words. Close friends often notice before the family does. Because symptoms are so vague, a diagnosis is rarely made at this stage. This early period may last one to two years.

Practical Solutions

- Keep a health diary: Record behaviour shifts, speech changes, and unusual actions to share with doctors.

- Encourage healthy living: Balanced meals, walks, and good sleep support wellbeing.

- Seek early medical checks: Early diagnosis helps families plan.

- Build awareness: Talk openly with close family so everyone understands.

Stage 2: Behavioural Shifts

Changes in behaviour now become clearer. The person may act impulsively, speak rudely without realising, or lose motivation to do things they once enjoyed. Speech becomes harder (simple words), with pauses or repeated phrases. Relationships can suffer as patience runs thin. Work performance may decline, often leading to stress or job loss. Families usually begin to seek medical advice here.

Practical Solutions

- Set routines: Daily schedules reduce stress and confusion.

- Limit triggers: Avoid situations that spark impulsive or rude behaviour.

- Simplify choices: Offer two options instead of many to reduce frustration.

- Reach out for support: Consider counselling or a carers’ group to manage stress.

Stage 3: Communication Decline

At this stage, language skills decline more rapidly and noticeably. The person may struggle to find words, mix up meanings, or misunderstand what is being said. Simple conversations become tiring and frustrating. Despite these difficulties, they may still recognise loved ones and join daily routines. Life expectancy at this point is often still ten (10) or more years from first symptoms.

Practical Solutions

- Use short sentences: Speak slowly and maintain eye contact.

- Add visual aids: Pictures or notes support understanding.

- Be patient with pauses: Give extra time for replies.

- Try speech therapy: Professionals can recommend helpful tools.

Stage 4: Daily Life Impact

Independence now begins to fade. Simple tasks such as cooking, shopping, handling money, or even dressing become challenging. Mistakes happen often, such as leaving the cooker on or misplacing items. This stage must start to prioritise safety in the living environment. Carers need to step in regularly, sometimes daily, 2 to 4 times. Frustration can grow for loved ones and their family. Social isolation is common, as outings feel harder to manage.

Practical Solutions

- Assist with daily tasks: Offer support with cooking, bills, and shopping.

- Check home safety: Remove tripping hazards, improve lighting, and lock away dangerous objects.

- Plan meals together: Use easy recipes or finger foods to promote independence.

- Consider respite care: Carers may need breaks to recharge.

Stage 5: Personality and Mood Shifts

This stage is emotionally tough for families. Strong and quick mood swings, bursts of anger, or a complete lack of interest in loved ones may appear. The person may lose empathy, seeming distant or self-negligent. Some may show inappropriate behaviour in public, which can be upsetting. For carers, this stage brings high stress. Life expectancy at this point is usually five (5) to eight (8) years remaining.

Practical Solutions

- Stay calm during outbursts: Avoid arguments and redirect with a gentle activity.

- Offer structured activities: Simple art, music, or puzzles can calm agitation.

- Prepare for public incidents: Carry a card that explains the person has dementia.

- Support carers: Share duties and seek help to prevent burnout.

Stage 6: Physical Decline

Physical abilities now decline alongside memory. Walking becomes stiff or unsteady, leading to falls. Muscle weakness and balance problems increase. Swallowing becomes harder, raising the risk of choking. Memory loss deepens, and the person may no longer recognise familiar faces. Infections, particularly chest infections, become more frequent. Round-the-clock care is often needed.

Practical Solutions

- Try physiotherapy: Gentle exercises maintain strength and balance.

- Monitor swallowing: Ask for safe food textures from a speech therapist.

- Prevent infections: Watch for chest or urinary infections and act early.

- Use mobility aids: Walking frames, grab bars, or wheelchairs support safety.

Stage 7: Late Stage

In the final stage, independence is fully lost. Speech disappears completely, and the person often cannot walk. They may spend most of their time in bed, relying on carers for feeding, washing, and all personal care. Swallowing is very difficult, and pneumonia (chest infections) is a major risk. At this point, survival is usually measured in months rather than years. Families often focus on comfort, dignity, and peace through palliative care.

Practical Solutions

- Focus on comfort: Use soothing music, gentle touch, and calm surroundings.

- Nutritional care: Use soft foods, thickened liquids, or feeding support as advised.

- Plan palliative care: Work with healthcare teams for dignity and peace.

- Offer family support: Counselling and bereavement services prepare carers for loss.

FTD Dementia Life Expectancy in Different Variants

Not all cases of frontotemporal dementia follow the same path. The variant of FTD strongly affects both symptoms and how long a person may live. Understanding these differences helps families prepare more realistically.

Behavioural Variant (bvFTD)

This is the most common form of frontotemporal dementia. It usually starts with strong changes in personality and behaviour. Families may notice a loss of empathy, poor judgment, or socially inappropriate actions. The person may become impulsive, overspend money, or withdraw from friends.

Life expectancy in behavioural variant FTD is typically seven to ten years after symptoms first appear. Because behaviour changes show earlier than memory problems, diagnosis can take time, meaning the illness may already be advanced when recognised. With good support, families can manage this stage, but caring often becomes challenging due to unpredictable moods and actions.

Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA)

In this variant, language is the main difficulty. At first, the person may only forget words or mix up meanings, but over time, speech and understanding decline. Eventually, they may lose the ability to hold conversations or recognise written words.

The life expectancy in PPA is often similar to that of behavioural variant FTD, averaging seven to nine years after symptoms. However, in some cases, decline may feel faster because losing language skills so early makes communication and care planning very difficult. Families often struggle with frustration, as their loved one understands less and less of what is said to them.

FTD with Motor Neurone Disease (FTD-MND)

This is the most aggressive form of FTD. It combines dementia symptoms with motor neurone disease (also called ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease). Alongside memory and behaviour changes, the person develops muscle weakness, stiffness, and difficulty swallowing or breathing.

Life expectancy is much shorter than in other forms—many people live only two to three years after symptoms begin. The physical decline is rapid, and carers often face overwhelming challenges, balancing both cognitive and motor symptoms. Families usually need early discussions with doctors about palliative care and breathing support.

Corticobasal Syndrome (CBS) and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP)

These are rare forms of FTD, but they mix movement problems with dementia symptoms. In Corticobasal Syndrome, one side of the body may become stiff and awkward, while thinking and behaviour decline. In Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, balance problems, falls, and eye movement difficulties appear early, alongside changes in mood and cognition.

Life expectancy in both is generally six to eight years after symptoms appear. The decline is often uneven, with some abilities preserved while others fail quickly. Falls, infections, and swallowing problems increase risks in later stages.

From the time of diagnosis, the average is often seven to eight years. This difference exists because symptoms often begin years before doctors recognise them.

Practical Steps for Families When Facing Frontotemporal Dementia

Understanding life expectancy in frontotemporal dementia is important, but knowing what to do is even more vital. Families cope better when they have clear, practical steps. These actions support both the person living with FTD and their carers at every stage of the journey.

Early Medical Planning

Getting medical support early makes a real difference. Families should not wait until symptoms worsen. Arrange a full care plan with a GP or dementia specialist as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed. This plan can guide decisions as the illness progresses.

Speech therapy may help when words begin to fade. A physiotherapist can support movement and reduce fall risks. Occupational therapists often suggest home adjustments that make daily life safer and easier. In some cases, doctors may prescribe medication for sleep problems, anxiety, or sudden mood changes. These steps create a foundation for a better quality of life.

Legal and Financial Planning

FTD often begins in midlife, so planning is vital. Families should discuss legal and financial matters early, while the person can still take part in decisions. Setting up powers of attorney for health and finance allows trusted family members to act on their behalf later.

Discussing wills and possible care costs can feel uncomfortable, but it removes stress in the future. Clear planning gives families peace of mind and ensures the person’s wishes are respected.

Daily Care Strategies

Day-to-day life with FTD can be unpredictable, but small adjustments help. Keeping routines simple and consistent lowers confusion and reduces stress for both the person and their carer.

Communication should be short and clear. Use one idea at a time and add gentle eye contact. Visual aids, like written reminders or pictures, can also guide daily activities.

Safety is another priority. Remove hazards such as loose rugs, sharp tools, or cluttered walkways. Good lighting and grab bars in bathrooms may prevent falls.

Eating can become a challenge. Offering finger foods or soft meals helps the person eat with more independence. A speech therapist can advise on safe textures if swallowing problems develop.

Support for Carers

Caring for someone with FTD is both rewarding and exhausting. Carers must look after themselves as well. Support groups, either online or local, provide a safe place to share experiences and advice.

Respite care gives carers short breaks to recharge. Even a few hours away each week can prevent burnout. Sharing tasks with other family members, friends, or community networks spreads the load. Carers should also make time for their own medical checks, exercise, and sleep. Healthy carers are better able to give loving care.

Planning for the Final Stage

Facing the late stage of FTD is never easy, but open conversations bring comfort. Families should talk early about end-of-life wishes. This might include preferences for care at home, in a hospice, or in a hospital.

Palliative care teams can provide pain relief, emotional support, and dignity in the final months. Comfort becomes the main goal. Gentle music, familiar voices, and soothing touch can reduce distress. Families should also seek counselling and bereavement support to prepare for loss and healing afterwards.

How Families Can Cope Emotionally

Facts and numbers give guidance, but emotions often weigh heavily. Hearing that a loved one’s life expectancy with frontotemporal dementia is limited can feel overwhelming. Families may experience shock, sadness, anger, or even guilt. These feelings are normal and deserve space. Emotional coping is not about removing pain but about learning to carry it with strength and love.

One of the most helpful steps is accepting support early. Families sometimes wait until they feel exhausted, but reaching out sooner makes the journey easier. Accepting help from relatives, friends, or professionals does not mean weakness. It shows wisdom and protects both the carer and the person living with dementia.

Another way to cope is by celebrating small joys. Even when memory fades or behaviour changes, moments of connection remain. Listening to music together, looking through old photos, or sharing a simple laugh can lift spirits. These short, happy moments become treasures, reminding families that love is still present.

It is also important to see beyond the illness. FTD changes behaviour, but the person is still there. Families often find comfort in focusing on the loved one’s past achievements, values, and personality. Remembering who they are, not just what the disease takes away, helps keep dignity and respect at the centre of care.

Grief will come in waves, even before the final stage. Families may grieve each change, such as when speech fades or independence is lost. Allowing space for these emotions prevents them from building up. At the same time, holding on to hope brings balance. Hope may not mean cure, but it can mean comfort, peace, or cherished memories.

Finally, carers must care for themselves emotionally. Those who join support groups, seek counselling, or talk openly with trusted friends often cope better. By sharing worries and receiving encouragement, they avoid isolation and burnout. Emotional strength allows carers to give steady, patient, and loving support throughout the journey.

Conclusion

Frontotemporal dementia life expectancy is usually between six and thirteen years, though it varies by type and stage. From diagnosis, many live about seven years. Families can plan better when they know the stages and likely outcomes.

Using clear terms like FTD dementia life expectancy and frontotemporal dementia stages life expectancy helps people find this information online.

Families should remember: life expectancy is not only about numbers. It is about planning, support, and dignity. With early steps, trusted care, and emotional strength, families can face FTD together.

This guide shows that while frontotemporal dementia life expectancy, there is still space for care, connection, and love.

“Get trusted advice on dementia care at home and practical tips for caring for someone with dementia at home—all in one place.”